Reflections

Below, please find art, prose and other reflections inspired by the Black lives in these documents. Thank you to our Community Circle and Advisory Board for allowing us to learn from you.

Fluidity by Dianne “Gumbo Marie” Honoré (Keywords Community Circle and Advisory Board Member, joined in 2022)

The Keywords project has been an insightful, deep learning process. Following our meetings I often reflect on the stories we review and the personal insights we share at days end. Reading through the documents gives a microscopic view of certain incidents and topics affecting colonial life in Louisiana but upon further investigation, digging through the verbiage, reading between the lines and angles of the written document we gain a well-rounded kaleidoscopic view of what it meant to live during colonial times. The keywords become gold nuggets in the process. I personally relate to several of the documented stories including Catharina’s Value. Being a Destrehan descendant it was moving to further explore that history. Also, Mama Comba’s Gumbeaux is significant in that I teach Creole foodways and descend from a long line of cooks from the enslaved to today.

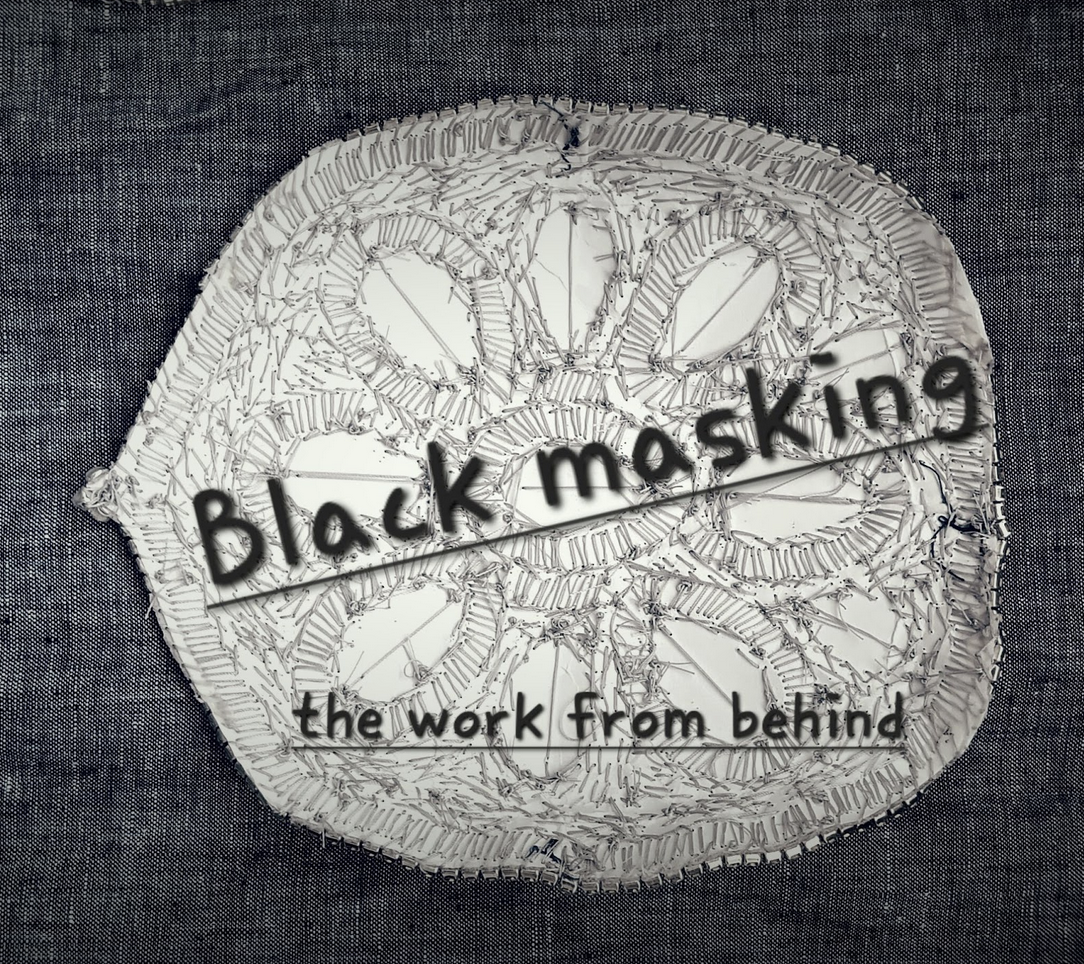

Last year, 2023 when we were asked to leave one word of insight at the table, I chose the word “fluidity”. After the day of discussion and discovery I was feeling the weight of our history and how we must keep moving forward in a positive way, to not get stuck in a dark space because our history can be heavy. That in turn influenced my Black Masking suit creation for the next year. The name of the suit is Fluidity. The suit is reflective of the overall healing message from being involved with the Keywords project. The workshops also influenced a program I produce called Healing Through History. I am reviving the program in September to include a full day of speakers, performances for healing purposes, discussions on learning about historical trauma and cultural healing. How we give voice, how we listen to them, how we document and make them more widely accessible for others to hear, how we take the lessons and heal moving forward. Moving forward through the waters of renewal. Rebaptizing the spirit.

Please see below for beaded pieces for the Fluidity suit. They are not yet complete and shaped, but the essence is present.

Famille of Louise Baptiste MEUILLON by Alex Lee (Keywords Community Circle and Advisory Board Member, joined in 2023)

An ancestor of mine who I’d like to highlight is Louise Baptiste MEUILLON, a free woman of color born circa 1802 in Louisiana. She passed away on April 27, 1862, in Opelousas, Louisiana. Louise was the daughter of Baptiste MEUILLON (CHEVAL), a free man of color and wealthy planter, born on the estate of Louis Augustin MEUILLON, a prominent planter.

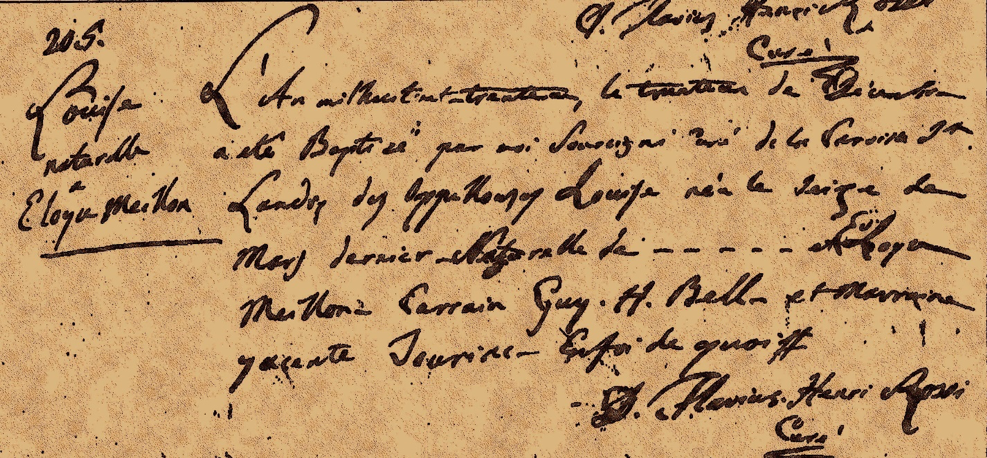

Louise was the mother of my direct ancestor Julie BIROTTE, a free woman of color, and daughter of Francois BIROTTE of New Orleans. The first document I discovered of Louise was her daughter Louise TAURIAC’s baptismal entry: MEUILLON, Louise (Eloise MEUILLON) b. 16 Mar. 1831 (Opel. Ch.: v. 3, p. 193). French: Louise, naturelle de Eloyce Meillon L’An mil huit centre trente et un, le trentième de décembre, a été baptisée par moi soussigné curé de la Paroisse St Landry —– Louise née le seize de mars dernier naturelle de ——- et Eloyce Meillon. Parrain Guy H. Bello Marraine Yacinthe Touriac En foi de quoi, Flavius Henri Rossi, curé English Translation: Louise, natural daughter of Eloyce Meuillon on the 30th day of December in the year 1831, was baptized by myself, undersigned priest of St Landry Parish, Louise, born on the 16th of last March, the natural daughter of (omitted) and Eloyce Meillon. Baptismal sponsors Guy H. Bell, Yacinthe (Hyacinthe/Hiacinthe) Touriac in witness whereof. Flavius Henri Rossi, Parish priest. The godparents of her daughter were Judge Guy H. BELL and Hyacinthe TAURIAC. Although the father was omitted, it was later discovered that Louise’s father was Louis TAURIAC, the child of Dr. TAURIAC, hence Louis’s sister being listed as the godmother…

Read the rest here

Never Can Say Goodbye by Kristina Kay Robinson (Keywords Community Circle and Advisory Board Member, joined in 2022)

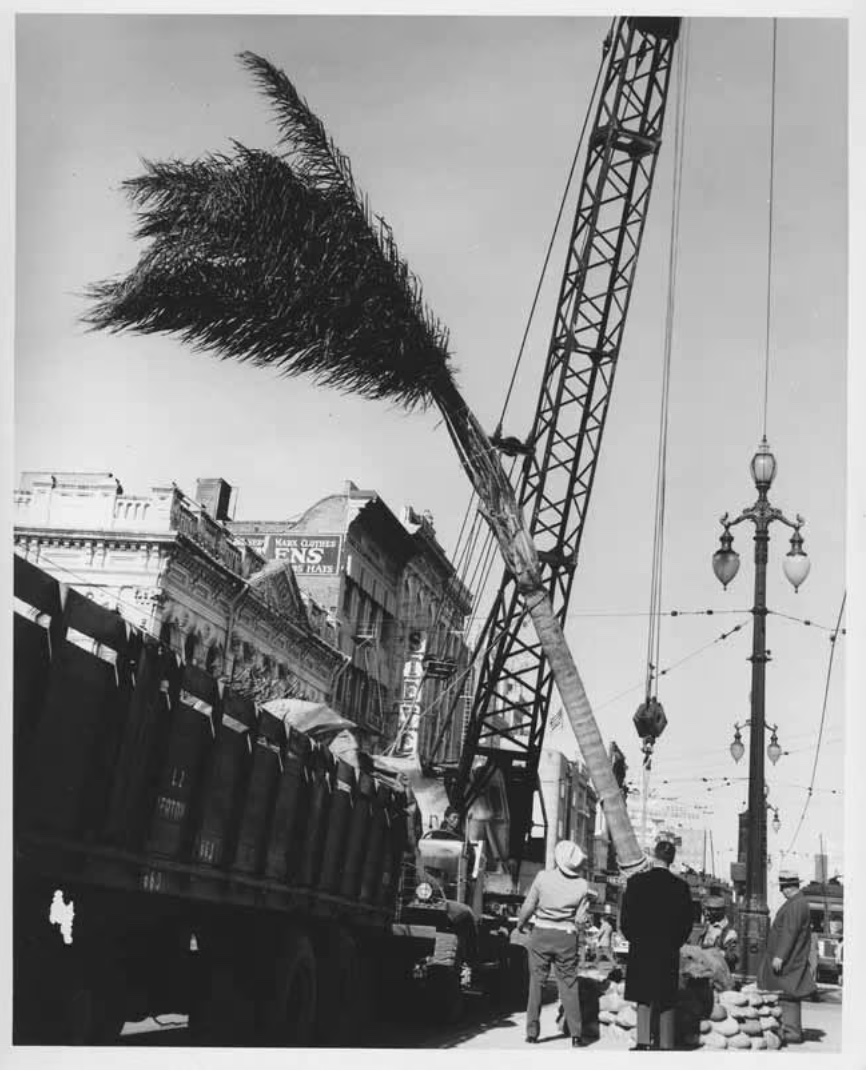

“Who’s that? Is that you?” a man asked, gesturing toward his phone, as I sat under the shade of a palm tree.

We were both out early, enjoying the couple of hours outside of the coffee shop before the heat became blistering. That morning I was reading about the growing cultural preservation movement among Afro-Iraqis. Descended from both enslaved East African populations and those of African descent already present in the Arabian Peninsula before the seventh century1, historically, Afro-Iraqis performed much of the labor of draining marshes, cultivating sugarcane, and date farming. I read about Iraq while I waited for my colleagues and a charter bus to arrive. We were heading two hours northwest to Opelousas, Louisiana, to visit the St. Landry Parish Archives with the project Keywords for Black Louisiana, led by Dr. Jessica Marie Johnson, author of the 2020 book Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World. Keyword’s researchers are working to digitize an annotated, transcribed, and translated collection of French and Spanish documents from eighteenth-century Louisiana that focus on the lives of both enslaved and free people of African descent.

The curious man stuck out his phone in my direction, pointing at a square on the California African American Museum’s Instagram grid. There I was in the film still, speaking to the camera on an almost floor to ceiling screen.

“No,” I answered. “People mistake us all the time though. She’s a woman I used to know.”

The white man stared.

I returned his gaze for a second, grateful for the partial obscuring of the palm’s shadow, and went quickly back to my book. I did not look back up again until he left.

The domestication of date palms began in the horn of Africa and Mesopotamia over four thousand years ago.

In his 2015 book Slaves of One Master: Globalization and Slavery in Arabia in the Age of Empire, Matthew S. Hopper dedicates the chapter “Slavery, Dates, and Globalization” to charting how the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century demand for dates in the United States fed the trading of forced human labor in Iraq and the Persian Gulf region. The port city of Basra, Iraq, became the epicenter for the trade in both the sticky fruits and humans. Date palms were brought to Spain by North African Muslims and the seeds made their way to the Americas via early Spanish explorers, their crews, and the Black people, enslaved and free, present on those voyages.

Louisiana in the 1730s required slaveholders to record and report when the people they held in bondage ran away. Through both the initial reports and later documents filed in their pursuit, compiled by Keywords for Black Louisiana, I encountered two Bambara men, Vulcan and Antoine (a double amputee), as well as a woman, Fanchon of the Senegal nation, who had fled to Cuba in the summer of 1739. The trio were assisted by another enslaved person, described as a “Spanish mulatress,” in stealing a pirogue and were never seen in Louisiana again. When their whereabouts were sought years later, it was reported that Fanchon had passed away, and that Antoine lived in the woods, while Vulcan sold beer in Havana. I wonder what names they called themselves, each other. What answers they gave the authorities, their neighbors when questioned about their identities.

Read the entire essay, published at The Burnaway here

The Black & Indigenous Research Adventure by Mona Lisa Saloy (Keywords Community Circle and Advisory Board Member, joined in 2022)

Africans, their Descendants & Indigenous Connections #HonorNativeLand!

Respectfully, I acknowledge the original native inhabitants of this land, air, water, and history of our beloved Louisiana, the first inhabitants of this place: the Atakapa, the Caddo, the Jena Band of Choctaw, Coushatta, the Chitimacha, Houma, the Natchez, the Tunica-Biloxi, for their timeless traditions of reverence to our cultures and space.

Black & Indigenous connections in the South, especially Louisiana

As an author, Folklorist, and scholar, it is often overwhelmingly shocking to comprehend the depth and breadth of cultural, creative, and social contributions of Blacks in the New World despite being denied ancestral culture, language, names, geographical, religious origins. In spite of this, on top of the economic, physical, political, religious, and social limitations enforced for centuries, so much beauty was and continues to be produced that makes the Americas what they are today: from Carnival in Trinidad and South America; to gospel music, jazz, R&B, rap; to soul food now cuisine; to masking; to Hoodoo or Vodun (although those inside the culture do not use those terms, because they are socially coded, it’s nearly impossible not to use them for reference here and even in scholarship); to fashion and style.

The first Africans, Moors, were brought by the Spanish to what later became South Carolina in 1526, by Lucas Vasquez de Ayllon, and also to Florida in 1565, by Admiral Don Pedro Menendez de Aviles. Those enslaved Moors of North Africa had a civilization already several hundred years old. They were highly-skilled craftsmen and artisans. Even the lovely arches and indigo tiles of Mexico are Moorish in origin. Dr. Ivan van Sertima teaches us in They Came Before Columbus, more Africans came by the 1500s and early 1600s. By the 1500s, once the Catholic Church declared that Indigenous were not to be enslaved (well, they knew nothing of the building trades colonial Europeans needed; plus, the massive agricultural imports from Africa needed tending), that decision fully-enforced the stealing of Africans to create wealth from white gold—sugar—or to be used in the building trades, in cattle driving and horse trading, including the herds used for the original westward expansion, alas, the Louisiana Purchase.

While some Black Creoles (descendants of mixed-enslaved Africans born in the New World), were aware that in Louisiana many of the Indigenous welcomed run-away enslaved Blacks into the palmetto swamps for survival, little is documented and explained about what significant connections were maintained, culturally and socially. Certainly, the Elder Grand Uncle of Tootie Montana knew this and masked in honor of African ancestral masking traditions and also honored those Indigenous who intermarried and welcomed early Blacks, even hid them for their survival. Such stories were passed down but unproven. What foodways traditions do we share from such intersection of cultures and eventually families? What other artistic traditions are handed down?

It is this intersection of discovery that led me to embrace the Keywords for Black Louisiana project and it’s development of the digital collection of enslaved testimony from French and Spanish Louisiana. Literally desperate to learn specifics of cultural, historic connections and legacies earned between African descendants and Indigenous of the New World, we began and dug deep. Of course, outside of wanting to answer the questions above, there’s a need to fill in the blanks for curricular updates in Black American literature courses as well as American Literature and Multi-cultural literature classes that are taught within the context of the forces that gave rise to those works….

As an author, Folklorist, scholar, Keywords’ Black & Indigenous project contributes to scholarly knowledge in English, Folklore, History, and literature, and to the general public’s understanding of this place. Final results will add to curricular reform and publications and is directly relevant to research themes of my work as an author of creative works, in Folklore, literature, and scholarship.

Langston Hughes’ “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” offered by Angela Proctor (Keywords Community Circle and Advisory Board Member, joined in 2023)